1968

As the year began, I had six months left at school and no idea what I would do next. In May I was guided toward the careers master who, on seeing the subjects I was taking, decided I should be an actuary. He had a contact at a big insurance company and arranged for me to have an interview. The interview took place on 6 June and by 12 June I had a job. I was joining the Royal Exchange Group as an actuarial trainee.

But I get ahead of myself. 21 March was a Thursday and a games day. It had rained all morning and at lunch time the notice went up that rugby was cancelled. Normally this would mean that we went home and I was walking through the hall to go downstairs into the crypt to collect my stuff when the master in charge of the senior colts team called me over. His team had a 7-a-side competition on the Saturday, he was going to train†and he wanted some opposition. His actual words were ď as you are one of the fastest guys in school, could you come and provide that oppositionĒ. Flattery got him everywhere and off I went.

We were the only boys at the field and we started by warming up and then went into a practice game. The ground was wet and, living up to me reputation and trying to test these boys to the maximum, I got the ball and immediately ran at their line. Seeing one of their team coming toward me to tackle, I performed a superb, and late, side step, fooling him completely. Sadly, I fooled my left foot too and, on the wet grass, it skidded off on its own. As I crashed to the ground I heard a definite crack and pain shot through that left foot. I think the others heard it too and the master came over quite concerned. If you make a fuss you become the centre of attention so I stood up and told him it was a little stiff but absolutely fine.

I played on, pretty immobile and no longer really providing any sort of opposition and we then went back to the pavilion to change. Problem number one; I couldnít get my boot off and some others had to cut bits off my boot to remove it. I still said it was fine and then walked from there to Finchley Road tube station, about 2 miles away and then, after the train ride, back home. Luckily this was a day that I hadnít taken the car.

When I got home, I told mother I had hurt my ankle but she just said she had told me rugby was a dangerous game. Fatherís reaction was different. He took one look and said we were going to the doctor. I have to admit it was a trifle swollen. I said it wasnít necessary and we eventually agreed that we would go to the doctor as long as I could drive. I couldnít, so father won and we definitely went to the doctor. He looked at it and said it might be broken but he couldnít tell. I needed an X-ray. He rang the local hospital but their x-ray machine was broken so it was decided that, next morning, we would go the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital at Stanmore for a proper x-ray.

We went there, I had the x-ray but I was told it was so badly bruised they couldnít tell if it was a broken bone or torn ligaments. A nurse then took me away and shaved my leg, as you do. She then applied some form of very sticky bandage to it. I thought she got unnecessarily carried away as the bandage went from foot, where the ankle was, to the top of my thigh where nothing broken could be found. I was told that this should stay on for 6 weeks; the bandage, my thigh is, I hope, a fairly permanent fixture. I could then remove it, the bandage notÖÖ.. and if, after doing so, I felt any pain or there was still any swelling, I should go back. I should also try to avoid putting too much weight on the foot.

In my earlier life, this would have meant time off school but, in my last years, I was enjoying it so much I was back on Monday. The six weeks would end just before the summer term started, and the cricket season began, so I wasnít too worried. Neither was I going back when I took the bandage off. Removing it was a task on its own. It took me 4 hours, lying in a bath of water to soak things but, eventually I was bandage-free. It hurt a bit to walk on and was still a little swollen but I put that down to inadvertently treading on a football while not having a kick-about as instructed. That ankle has been a problem ever since. The moral, children is be sensible and look after yourself but donít ever follow the ways of an idiot.

This was a little bit of an injury-prone period for me but before I tell you more about that, letís leave school for the last time. I spent the summer playing in the 3rd eleven for cricket, playing every game and also chose to play in a house match on the afternoon of my history ďAĒ level. To allow me to take it, it was re-arranged for the morning, and then I was figuratively chained to a teacher, funnily enough the guy who asked me to provide that opposition, and we lunched together and I, who had the car that day, then drove him to the field. At 2pm, when the exam started, my Siamese twin and I parted company and I could talk to people again. We won the game, a semi-final match and I didnít fail the ďAĒ level either; note the order I told you this.

Talking of lunch reminds me that this occasion was only the second time I had lunch at school in my whole time there, following my return. I went the first day but was a bit late on the second and too embarrassed to go. Then I had not got a regular place to sit, so I never went again. There were two lunches at 12.50pm or 1.25pm so I donít think anyone really noticed. But it did mean that for five years I lived on 2 meals a day.

Another occurrence during these ďAĒ levels was that my grandpa died. He had been taken to hospital in the May and when I went with mother to see him in early June, he looked terrible. He was painfully thin and very pale in colour. Nevertheless we talked about my upcoming interview and he seemed interested. Over the next few weeks he deteriorated further, becoming confused and refusing to eat and, on June 26, the day before another ďAĒ level, he died. Instead of revising I spent all that day ferrying mother and her sister back and forth to hospitals, registrars and home. His cremation took place a week later but my sister and I didnít go.

I had a medical for my job on 10 July, they didnít check ankles, and then on 17 July 1968, my 19th birthday, I attended school for the final time on my final speech day, which we always held at the end of the summer term. It was such an important event that even the Prime Ministerís wife attended. I may be taking a little bit of temporal licence here as, although two of Harold Wilsonís sons did attend the same school, and Mary did come to speech days, I think they had both left by then. Still the thought was there. It was on this occasion that my father, after much persuasion from mother, had sidled up to the Head to thank him for all he had done for me. In 1981, just before he died and when we used to have long chats, father told me that one of his proudest moments had been when, at this speech day, the Head had told him that, in his opinion, I was one of the bravest boys he had ever had the pleasure of having at his school. He felt that conquering my very obvious fears amounted to a display of tremendous courage. I had never thought of it that way; all I was struggling to do was the same as every other boy did with no problems. It couldnít be courageous to be normal. The Head felt otherwise and I have remembered those comments through the rest of my life.

I also wrote a bit about him in my first piece on education. It read as follows:- ďI had a fantastic education in a great school. On my final day there, the head, an amazing guy called David Black-Hawkins, came over and spoke to my father. Later the gist of the conversation was told to me. My dad said that dear old Mr Black Hawkins had told him that he didnít really care what qualifications pupils had when they left his school as long as he and his staff had equipped them to enjoy their lives and deal with any problems they might encounter. ĎI want them to believe in themselves whatever any results may tell themí, he said, Ďbecause if they do that, then they will achieve everything they wantí. I can assure everyone that both this snippet and his belief in my courage were a great influence on the rest of my life. If you donít believe that what happens and is said to you early in life can influence your whole life, you and I are at odds, mate.

This year we went on holiday alone, just the four of us. We went, again, to Norfolk, staying at The Forge in Southrepps, where we had spent the last 3 holidays. I really loved the rural charm that was on offer and although on certain beaches, Cromer being one, you had to sit with your back to the sea to face the midday sun, we always had a great time. It may look, in this picture, as though that ankle injury is playing up and I have had to adopt a peculiar stance in order to compensate for the pain I was still feeling. In fact, this wasnít true. You can also note that I had now gone some way toward understanding the need for less formal attire on a holiday although, it would appear, mother and father had not.

This year we went on holiday alone, just the four of us. We went, again, to Norfolk, staying at The Forge in Southrepps, where we had spent the last 3 holidays. I really loved the rural charm that was on offer and although on certain beaches, Cromer being one, you had to sit with your back to the sea to face the midday sun, we always had a great time. It may look, in this picture, as though that ankle injury is playing up and I have had to adopt a peculiar stance in order to compensate for the pain I was still feeling. In fact, this wasnít true. You can also note that I had now gone some way toward understanding the need for less formal attire on a holiday although, it would appear, mother and father had not.

There, my lovable little sister is also posing in a strange way and so I think this may have been some sort of dare to see who could look the most stupid. Once again, as so often in her life, she has snatched victory from the jaws of defeat, and with de feet in that position who could argue. Skirts a bit short Elizabeth, I can hear mother saying. Talking of being short, the other photo seems to portray me as some sort of giant as I am head-high to mother while bending my legs. I should point out that, at this stage in her life, mother was only 4ft 11in having lost 3in while she was so ill, before being diagnosed as a coeliac.

And that life, that I mentioned my old Head had influenced, was now entering a brand new phase. On 12 August 1968, I started work for the Royal Exchange in an office in Cheapside in London in their life quotations department. I was in the section with three others, all working under an Assistant Superintendent. Each morning we would come in at 9.00am and sign in. If someone had not done so by 9.10am, then the guy in charge of all people on that floor, there were other sections there, would wander round and try to find out why someone was missing. My starting salary was £625 per annum and out of each monthly salary cheque I gave mother 25% for my keep. This is what she claimed was returned to me when I came to buy my first house.

Of the 3 others in the section, one was about my age and would only be there for a few more weeks as he had done the job as a gap year before staring uni. Another had come into the job about 2 years ago from uni while the third guy, the section leader was in his early thirties. My boss, the Assistant Superintendent was a guy in his late forties, a chain smoker, who had, so I was told, been a tail gunner in a Lancaster bomber during the war. He was incredibly quiet and shy, I identified with him immediately, and I found out later he had failed his actuarial exams in the past. I also discovered that even the Chief Actuary would often ask him to help solve some problem, write some letter etc. Exams, I realised, didnít mean you knew everything but did seem to influence your chances of promotion; this guy could easily have had a higher position based on knowledge and ability but he couldnít be promoted without his exams.

I learnt the job quickly, I had no choice. When I arrived the older guy was already working out his notice and would leave before the end of August. The soon-to-be student was leaving early September and, on the day I arrived (absolutely no connection), the other guy handed in his notice to begin a new job elsewhere. In early September, apart from my boss, I was the only one there for a week for although they transferred in a guy from another section he was on holiday until mid September. For the next year, this guy, who weirdly had worked under my father for a few years in the civil service, and I, together with our boss, did all the work in that section.

Our job was to calculate premiums and annuity rates for non-standard life policies, the standard ones were in our rate book which all branches and agents had. We did the unusual ones. We needed to use life expectancy tables, compound interest tables and we had calculators and one of them was electric. Wow. I loved it, the only blight being that they thought I would be taking the actuarial exams but, when my ďAĒ level results came through my grade in statistics wasnít good enough. I then said I would resit next year and then start the actuarial exams. I never did but remained in the actuarial section till I left in 1978. I was constantly promoted up the ranks, sometimes because the high-flying would-be actuaries left once qualified†to join another company.

On 20 October 1968 I was sent with other new recruits from all over the country on a training course where we stayed, for the week, in a hotel in East Mosley. I was coping far better with people now but still kept myself to myself where possible. I enjoyed the week, declined the invitation of the northern lads to go to a strip club, which may surprise people as everyone else did go. In fact Bob Beamon was so surprised he jumped nearly 30 ft. Much of that week, in the evenings and excluding the strip club visit, was spent watching the Mexico Olympics well into the night. I also discovered, from the other head office recruit, that, as an actuarial trainee, I had special privileges. They all had to arrive at 8.00am to assist in sorting the post; no one asked me to do that.

Talking of sport, that part of my life had changed too. On 24 August I played my first cricket game for the old boys but it was heading toward the end of the season and I only played one more. On 7 September 1968 I also played my first game of rugby for the old boys. I continued for the whole season, also going to training twice a week. My life was good. In November while playing a hospital team, I fell awkwardly and dislocated my right shoulder. The other team had doctors, or trainee doctors, and the shoulder was quickly put back but I was advised to get it checked out. I forgot. Luckily all my files at work were on my left side and it was only in the next cricket season I found out that, although I could still bowl, I couldnít impart any spin on the ball. Moral; donít follow an idiot.

There, my lovable little sister is also posing in a strange way and so I think this may have been some sort of dare to see who could look the most stupid. Once again, as so often in her life, she has snatched victory from the jaws of defeat, and with de feet in that position who could argue. Skirts a bit short Elizabeth, I can hear mother saying. Talking of being short, the other photo seems to portray me as some sort of giant as I am head-high to mother while bending my legs. I should point out that, at this stage in her life, mother was only 4ft 11in having lost 3in while she was so ill, before being diagnosed as a coeliac.

And that life, that I mentioned my old Head had influenced, was now entering a brand new phase. On 12 August 1968, I started work for the Royal Exchange in an office in Cheapside in London in their life quotations department. I was in the section with three others, all working under an Assistant Superintendent. Each morning we would come in at 9.00am and sign in. If someone had not done so by 9.10am, then the guy in charge of all people on that floor, there were other sections there, would wander round and try to find out why someone was missing. My starting salary was £625 per annum and out of each monthly salary cheque I gave mother 25% for my keep. This is what she claimed was returned to me when I came to buy my first house.

Of the 3 others in the section, one was about my age and would only be there for a few more weeks as he had done the job as a gap year before staring uni. Another had come into the job about 2 years ago from uni while the third guy, the section leader was in his early thirties. My boss, the Assistant Superintendent was a guy in his late forties, a chain smoker, who had, so I was told, been a tail gunner in a Lancaster bomber during the war. He was incredibly quiet and shy, I identified with him immediately, and I found out later he had failed his actuarial exams in the past. I also discovered that even the Chief Actuary would often ask him to help solve some problem, write some letter etc. Exams, I realised, didnít mean you knew everything but did seem to influence your chances of promotion; this guy could easily have had a higher position based on knowledge and ability but he couldnít be promoted without his exams.

I learnt the job quickly, I had no choice. When I arrived the older guy was already working out his notice and would leave before the end of August. The soon-to-be student was leaving early September and, on the day I arrived (absolutely no connection), the other guy handed in his notice to begin a new job elsewhere. In early September, apart from my boss, I was the only one there for a week for although they transferred in a guy from another section he was on holiday until mid September. For the next year, this guy, who weirdly had worked under my father for a few years in the civil service, and I, together with our boss, did all the work in that section.

Our job was to calculate premiums and annuity rates for non-standard life policies, the standard ones were in our rate book which all branches and agents had. We did the unusual ones. We needed to use life expectancy tables, compound interest tables and we had calculators and one of them was electric. Wow. I loved it, the only blight being that they thought I would be taking the actuarial exams but, when my ďAĒ level results came through my grade in statistics wasnít good enough. I then said I would resit next year and then start the actuarial exams. I never did but remained in the actuarial section till I left in 1978. I was constantly promoted up the ranks, sometimes because the high-flying would-be actuaries left once qualified†to join another company.

On 20 October 1968 I was sent with other new recruits from all over the country on a training course where we stayed, for the week, in a hotel in East Mosley. I was coping far better with people now but still kept myself to myself where possible. I enjoyed the week, declined the invitation of the northern lads to go to a strip club, which may surprise people as everyone else did go. In fact Bob Beamon was so surprised he jumped nearly 30 ft. Much of that week, in the evenings and excluding the strip club visit, was spent watching the Mexico Olympics well into the night. I also discovered, from the other head office recruit, that, as an actuarial trainee, I had special privileges. They all had to arrive at 8.00am to assist in sorting the post; no one asked me to do that.

Talking of sport, that part of my life had changed too. On 24 August I played my first cricket game for the old boys but it was heading toward the end of the season and I only played one more. On 7 September 1968 I also played my first game of rugby for the old boys. I continued for the whole season, also going to training twice a week. My life was good. In November while playing a hospital team, I fell awkwardly and dislocated my right shoulder. The other team had doctors, or trainee doctors, and the shoulder was quickly put back but I was advised to get it checked out. I forgot. Luckily all my files at work were on my left side and it was only in the next cricket season I found out that, although I could still bowl, I couldnít impart any spin on the ball. Moral; donít follow an idiot.

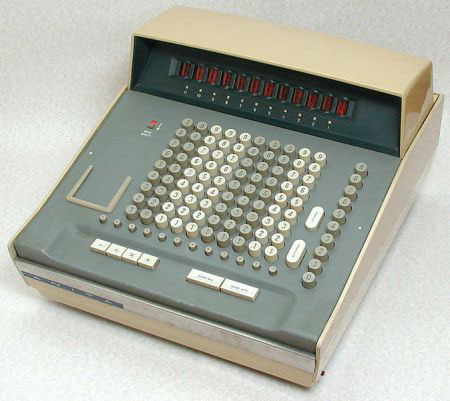

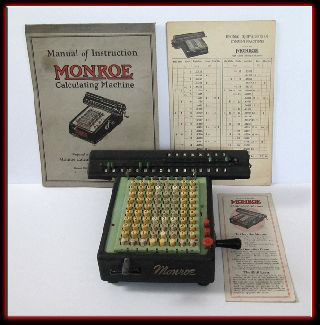

My year ended with two contrasting incidents. In November, 3 months into my job and still pretty shy, I received a call, with no one else in the office, from a lady who said she had some policies with us but she was also running a calculating business and had been given a task of doing a job but she needed compound interest tables and she had none, did we know where she could get any? You have to remember that in these stone-age technological times, calculators were fairly new and many firms would farm out their calculating jobs to agencies where women would use comptometers. We had two such people in our office and they could add, subtract, multiply and divide sets of figures at incredible speed. This picture shows a comptometer.

My year ended with two contrasting incidents. In November, 3 months into my job and still pretty shy, I received a call, with no one else in the office, from a lady who said she had some policies with us but she was also running a calculating business and had been given a task of doing a job but she needed compound interest tables and she had none, did we know where she could get any? You have to remember that in these stone-age technological times, calculators were fairly new and many firms would farm out their calculating jobs to agencies where women would use comptometers. We had two such people in our office and they could add, subtract, multiply and divide sets of figures at incredible speed. This picture shows a comptometer.

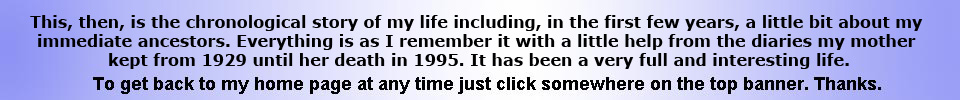

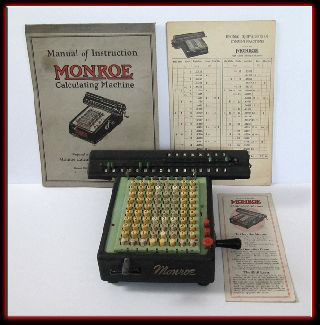

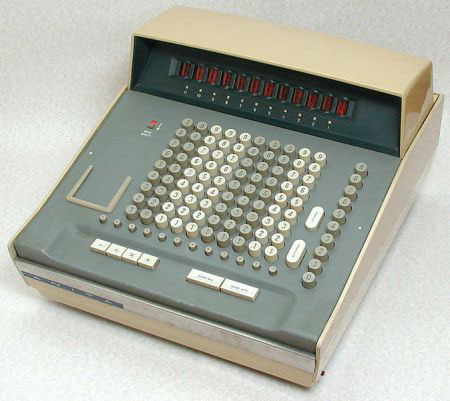

Because the older guy in the section left first, I took over his electric calculator which was almost identical to the one in the picture on the right. It could do all sorts of calculations but it had a habit of getting stuck and whirring around endlessly and aimlessly. Of course this alerted everyone else in the office to the fact that something was wrong and, although I knew I had done nothing to cause this outburst, I still blushed when it happened. Sometimes a simple unplugging would solve it, sometimes a gentle thump and sometimes the engineer was needed. The fact that it happened to others too made no difference to my embarrassment.

Because the older guy in the section left first, I took over his electric calculator which was almost identical to the one in the picture on the right. It could do all sorts of calculations but it had a habit of getting stuck and whirring around endlessly and aimlessly. Of course this alerted everyone else in the office to the fact that something was wrong and, although I knew I had done nothing to cause this outburst, I still blushed when it happened. Sometimes a simple unplugging would solve it, sometimes a gentle thump and sometimes the engineer was needed. The fact that it happened to others too made no difference to my embarrassment.

Less favoured members of staff would have hand-operated machines which were slower but when they jammed no-one knew, until you were seen banging it hard. But to return to this lady and her problem. I found out where she could buy a compound interest book, invited her round to show her the basics of using it and, in return she gave me £5 and bought me a new tie as she said that the rather staid one I was wearing didnít fit my more outrageous, for the city of London in 1968, shirts and suits. She continued to keep in touch for several years. Telling me once that my help had allowed her to build her newly formed business into a very profitable concern. What happened to her when computers really took over I have no idea.

I donít think I mentioned that my father never drank, apart from a glass of cider at Christmas, so when I was invited to drinks at work I, initially, used to make up an excuse because, quite simply, I had never ordered in a pub and didnít really know what to ask for anyway. Mother had initiated my drinking at home but I used to join her and friends for a gin and bitter lemon and somehow knew that might not look too good among the lads. My new colleague, and fatherís ex-colleague, solved this by taking me out at Christmas. Motherís diary notes ďRichard had Christmas drinks, he drank many pintsĒ.

The year ended with the beginnings of my panic attacks, nowadays perceived as a mental health problem. I remember the occasion perfectly. It was Boxing Day. We were sitting at the table while father carved the cold turkey. For a second, I drifted off. I knew I had missed something and immediately panicked. I got up from the table and went to my bedroom and stayed there for the rest of the day. It was a feeling I hated. I have to be in control of my mind 100%, 24/7, which is one reason why I never, ever tried any drugs of any sort. So, if I thought I had lost it, for even that brief second, something was wrong. In later years I would announce I was going to die. In later years things were far worse. This time I just needed space to lie down. On reflection, I believe I was over tired. Five months in a very stressful job, being thrown in at the deep end, the excitement of Christmas plus those first drinks had all contributed to my tiredness and all it was is that for that one second, my body shut down.

These panics returned big time in 1974 and again I now know why but more of that later.

Less favoured members of staff would have hand-operated machines which were slower but when they jammed no-one knew, until you were seen banging it hard. But to return to this lady and her problem. I found out where she could buy a compound interest book, invited her round to show her the basics of using it and, in return she gave me £5 and bought me a new tie as she said that the rather staid one I was wearing didnít fit my more outrageous, for the city of London in 1968, shirts and suits. She continued to keep in touch for several years. Telling me once that my help had allowed her to build her newly formed business into a very profitable concern. What happened to her when computers really took over I have no idea.

I donít think I mentioned that my father never drank, apart from a glass of cider at Christmas, so when I was invited to drinks at work I, initially, used to make up an excuse because, quite simply, I had never ordered in a pub and didnít really know what to ask for anyway. Mother had initiated my drinking at home but I used to join her and friends for a gin and bitter lemon and somehow knew that might not look too good among the lads. My new colleague, and fatherís ex-colleague, solved this by taking me out at Christmas. Motherís diary notes ďRichard had Christmas drinks, he drank many pintsĒ.

The year ended with the beginnings of my panic attacks, nowadays perceived as a mental health problem. I remember the occasion perfectly. It was Boxing Day. We were sitting at the table while father carved the cold turkey. For a second, I drifted off. I knew I had missed something and immediately panicked. I got up from the table and went to my bedroom and stayed there for the rest of the day. It was a feeling I hated. I have to be in control of my mind 100%, 24/7, which is one reason why I never, ever tried any drugs of any sort. So, if I thought I had lost it, for even that brief second, something was wrong. In later years I would announce I was going to die. In later years things were far worse. This time I just needed space to lie down. On reflection, I believe I was over tired. Five months in a very stressful job, being thrown in at the deep end, the excitement of Christmas plus those first drinks had all contributed to my tiredness and all it was is that for that one second, my body shut down.

These panics returned big time in 1974 and again I now know why but more of that later.

This year we went on holiday alone, just the four of us. We went, again, to Norfolk, staying at The Forge in Southrepps, where we had spent the last 3 holidays. I really loved the rural charm that was on offer and although on certain beaches, Cromer being one, you had to sit with your back to the sea to face the midday sun, we always had a great time. It may look, in this picture, as though that ankle injury is playing up and I have had to adopt a peculiar stance in order to compensate for the pain I was still feeling. In fact, this wasnít true. You can also note that I had now gone some way toward understanding the need for less formal attire on a holiday although, it would appear, mother and father had not.

This year we went on holiday alone, just the four of us. We went, again, to Norfolk, staying at The Forge in Southrepps, where we had spent the last 3 holidays. I really loved the rural charm that was on offer and although on certain beaches, Cromer being one, you had to sit with your back to the sea to face the midday sun, we always had a great time. It may look, in this picture, as though that ankle injury is playing up and I have had to adopt a peculiar stance in order to compensate for the pain I was still feeling. In fact, this wasnít true. You can also note that I had now gone some way toward understanding the need for less formal attire on a holiday although, it would appear, mother and father had not.

There, my lovable little sister is also posing in a strange way and so I think this may have been some sort of dare to see who could look the most stupid. Once again, as so often in her life, she has snatched victory from the jaws of defeat, and with de feet in that position who could argue. Skirts a bit short Elizabeth, I can hear mother saying. Talking of being short, the other photo seems to portray me as some sort of giant as I am head-high to mother while bending my legs. I should point out that, at this stage in her life, mother was only 4ft 11in having lost 3in while she was so ill, before being diagnosed as a coeliac.

And that life, that I mentioned my old Head had influenced, was now entering a brand new phase. On 12 August 1968, I started work for the Royal Exchange in an office in Cheapside in London in their life quotations department. I was in the section with three others, all working under an Assistant Superintendent. Each morning we would come in at 9.00am and sign in. If someone had not done so by 9.10am, then the guy in charge of all people on that floor, there were other sections there, would wander round and try to find out why someone was missing. My starting salary was £625 per annum and out of each monthly salary cheque I gave mother 25% for my keep. This is what she claimed was returned to me when I came to buy my first house.

Of the 3 others in the section, one was about my age and would only be there for a few more weeks as he had done the job as a gap year before staring uni. Another had come into the job about 2 years ago from uni while the third guy, the section leader was in his early thirties. My boss, the Assistant Superintendent was a guy in his late forties, a chain smoker, who had, so I was told, been a tail gunner in a Lancaster bomber during the war. He was incredibly quiet and shy, I identified with him immediately, and I found out later he had failed his actuarial exams in the past. I also discovered that even the Chief Actuary would often ask him to help solve some problem, write some letter etc. Exams, I realised, didnít mean you knew everything but did seem to influence your chances of promotion; this guy could easily have had a higher position based on knowledge and ability but he couldnít be promoted without his exams.

I learnt the job quickly, I had no choice. When I arrived the older guy was already working out his notice and would leave before the end of August. The soon-to-be student was leaving early September and, on the day I arrived (absolutely no connection), the other guy handed in his notice to begin a new job elsewhere. In early September, apart from my boss, I was the only one there for a week for although they transferred in a guy from another section he was on holiday until mid September. For the next year, this guy, who weirdly had worked under my father for a few years in the civil service, and I, together with our boss, did all the work in that section.

Our job was to calculate premiums and annuity rates for non-standard life policies, the standard ones were in our rate book which all branches and agents had. We did the unusual ones. We needed to use life expectancy tables, compound interest tables and we had calculators and one of them was electric. Wow. I loved it, the only blight being that they thought I would be taking the actuarial exams but, when my ďAĒ level results came through my grade in statistics wasnít good enough. I then said I would resit next year and then start the actuarial exams. I never did but remained in the actuarial section till I left in 1978. I was constantly promoted up the ranks, sometimes because the high-flying would-be actuaries left once qualified†to join another company.

On 20 October 1968 I was sent with other new recruits from all over the country on a training course where we stayed, for the week, in a hotel in East Mosley. I was coping far better with people now but still kept myself to myself where possible. I enjoyed the week, declined the invitation of the northern lads to go to a strip club, which may surprise people as everyone else did go. In fact Bob Beamon was so surprised he jumped nearly 30 ft. Much of that week, in the evenings and excluding the strip club visit, was spent watching the Mexico Olympics well into the night. I also discovered, from the other head office recruit, that, as an actuarial trainee, I had special privileges. They all had to arrive at 8.00am to assist in sorting the post; no one asked me to do that.

Talking of sport, that part of my life had changed too. On 24 August I played my first cricket game for the old boys but it was heading toward the end of the season and I only played one more. On 7 September 1968 I also played my first game of rugby for the old boys. I continued for the whole season, also going to training twice a week. My life was good. In November while playing a hospital team, I fell awkwardly and dislocated my right shoulder. The other team had doctors, or trainee doctors, and the shoulder was quickly put back but I was advised to get it checked out. I forgot. Luckily all my files at work were on my left side and it was only in the next cricket season I found out that, although I could still bowl, I couldnít impart any spin on the ball. Moral; donít follow an idiot.

There, my lovable little sister is also posing in a strange way and so I think this may have been some sort of dare to see who could look the most stupid. Once again, as so often in her life, she has snatched victory from the jaws of defeat, and with de feet in that position who could argue. Skirts a bit short Elizabeth, I can hear mother saying. Talking of being short, the other photo seems to portray me as some sort of giant as I am head-high to mother while bending my legs. I should point out that, at this stage in her life, mother was only 4ft 11in having lost 3in while she was so ill, before being diagnosed as a coeliac.

And that life, that I mentioned my old Head had influenced, was now entering a brand new phase. On 12 August 1968, I started work for the Royal Exchange in an office in Cheapside in London in their life quotations department. I was in the section with three others, all working under an Assistant Superintendent. Each morning we would come in at 9.00am and sign in. If someone had not done so by 9.10am, then the guy in charge of all people on that floor, there were other sections there, would wander round and try to find out why someone was missing. My starting salary was £625 per annum and out of each monthly salary cheque I gave mother 25% for my keep. This is what she claimed was returned to me when I came to buy my first house.

Of the 3 others in the section, one was about my age and would only be there for a few more weeks as he had done the job as a gap year before staring uni. Another had come into the job about 2 years ago from uni while the third guy, the section leader was in his early thirties. My boss, the Assistant Superintendent was a guy in his late forties, a chain smoker, who had, so I was told, been a tail gunner in a Lancaster bomber during the war. He was incredibly quiet and shy, I identified with him immediately, and I found out later he had failed his actuarial exams in the past. I also discovered that even the Chief Actuary would often ask him to help solve some problem, write some letter etc. Exams, I realised, didnít mean you knew everything but did seem to influence your chances of promotion; this guy could easily have had a higher position based on knowledge and ability but he couldnít be promoted without his exams.

I learnt the job quickly, I had no choice. When I arrived the older guy was already working out his notice and would leave before the end of August. The soon-to-be student was leaving early September and, on the day I arrived (absolutely no connection), the other guy handed in his notice to begin a new job elsewhere. In early September, apart from my boss, I was the only one there for a week for although they transferred in a guy from another section he was on holiday until mid September. For the next year, this guy, who weirdly had worked under my father for a few years in the civil service, and I, together with our boss, did all the work in that section.

Our job was to calculate premiums and annuity rates for non-standard life policies, the standard ones were in our rate book which all branches and agents had. We did the unusual ones. We needed to use life expectancy tables, compound interest tables and we had calculators and one of them was electric. Wow. I loved it, the only blight being that they thought I would be taking the actuarial exams but, when my ďAĒ level results came through my grade in statistics wasnít good enough. I then said I would resit next year and then start the actuarial exams. I never did but remained in the actuarial section till I left in 1978. I was constantly promoted up the ranks, sometimes because the high-flying would-be actuaries left once qualified†to join another company.

On 20 October 1968 I was sent with other new recruits from all over the country on a training course where we stayed, for the week, in a hotel in East Mosley. I was coping far better with people now but still kept myself to myself where possible. I enjoyed the week, declined the invitation of the northern lads to go to a strip club, which may surprise people as everyone else did go. In fact Bob Beamon was so surprised he jumped nearly 30 ft. Much of that week, in the evenings and excluding the strip club visit, was spent watching the Mexico Olympics well into the night. I also discovered, from the other head office recruit, that, as an actuarial trainee, I had special privileges. They all had to arrive at 8.00am to assist in sorting the post; no one asked me to do that.

Talking of sport, that part of my life had changed too. On 24 August I played my first cricket game for the old boys but it was heading toward the end of the season and I only played one more. On 7 September 1968 I also played my first game of rugby for the old boys. I continued for the whole season, also going to training twice a week. My life was good. In November while playing a hospital team, I fell awkwardly and dislocated my right shoulder. The other team had doctors, or trainee doctors, and the shoulder was quickly put back but I was advised to get it checked out. I forgot. Luckily all my files at work were on my left side and it was only in the next cricket season I found out that, although I could still bowl, I couldnít impart any spin on the ball. Moral; donít follow an idiot.

My year ended with two contrasting incidents. In November, 3 months into my job and still pretty shy, I received a call, with no one else in the office, from a lady who said she had some policies with us but she was also running a calculating business and had been given a task of doing a job but she needed compound interest tables and she had none, did we know where she could get any? You have to remember that in these stone-age technological times, calculators were fairly new and many firms would farm out their calculating jobs to agencies where women would use comptometers. We had two such people in our office and they could add, subtract, multiply and divide sets of figures at incredible speed. This picture shows a comptometer.

My year ended with two contrasting incidents. In November, 3 months into my job and still pretty shy, I received a call, with no one else in the office, from a lady who said she had some policies with us but she was also running a calculating business and had been given a task of doing a job but she needed compound interest tables and she had none, did we know where she could get any? You have to remember that in these stone-age technological times, calculators were fairly new and many firms would farm out their calculating jobs to agencies where women would use comptometers. We had two such people in our office and they could add, subtract, multiply and divide sets of figures at incredible speed. This picture shows a comptometer.

Because the older guy in the section left first, I took over his electric calculator which was almost identical to the one in the picture on the right. It could do all sorts of calculations but it had a habit of getting stuck and whirring around endlessly and aimlessly. Of course this alerted everyone else in the office to the fact that something was wrong and, although I knew I had done nothing to cause this outburst, I still blushed when it happened. Sometimes a simple unplugging would solve it, sometimes a gentle thump and sometimes the engineer was needed. The fact that it happened to others too made no difference to my embarrassment.

Because the older guy in the section left first, I took over his electric calculator which was almost identical to the one in the picture on the right. It could do all sorts of calculations but it had a habit of getting stuck and whirring around endlessly and aimlessly. Of course this alerted everyone else in the office to the fact that something was wrong and, although I knew I had done nothing to cause this outburst, I still blushed when it happened. Sometimes a simple unplugging would solve it, sometimes a gentle thump and sometimes the engineer was needed. The fact that it happened to others too made no difference to my embarrassment.

Less favoured members of staff would have hand-operated machines which were slower but when they jammed no-one knew, until you were seen banging it hard. But to return to this lady and her problem. I found out where she could buy a compound interest book, invited her round to show her the basics of using it and, in return she gave me £5 and bought me a new tie as she said that the rather staid one I was wearing didnít fit my more outrageous, for the city of London in 1968, shirts and suits. She continued to keep in touch for several years. Telling me once that my help had allowed her to build her newly formed business into a very profitable concern. What happened to her when computers really took over I have no idea.

I donít think I mentioned that my father never drank, apart from a glass of cider at Christmas, so when I was invited to drinks at work I, initially, used to make up an excuse because, quite simply, I had never ordered in a pub and didnít really know what to ask for anyway. Mother had initiated my drinking at home but I used to join her and friends for a gin and bitter lemon and somehow knew that might not look too good among the lads. My new colleague, and fatherís ex-colleague, solved this by taking me out at Christmas. Motherís diary notes ďRichard had Christmas drinks, he drank many pintsĒ.

The year ended with the beginnings of my panic attacks, nowadays perceived as a mental health problem. I remember the occasion perfectly. It was Boxing Day. We were sitting at the table while father carved the cold turkey. For a second, I drifted off. I knew I had missed something and immediately panicked. I got up from the table and went to my bedroom and stayed there for the rest of the day. It was a feeling I hated. I have to be in control of my mind 100%, 24/7, which is one reason why I never, ever tried any drugs of any sort. So, if I thought I had lost it, for even that brief second, something was wrong. In later years I would announce I was going to die. In later years things were far worse. This time I just needed space to lie down. On reflection, I believe I was over tired. Five months in a very stressful job, being thrown in at the deep end, the excitement of Christmas plus those first drinks had all contributed to my tiredness and all it was is that for that one second, my body shut down.

These panics returned big time in 1974 and again I now know why but more of that later.

Less favoured members of staff would have hand-operated machines which were slower but when they jammed no-one knew, until you were seen banging it hard. But to return to this lady and her problem. I found out where she could buy a compound interest book, invited her round to show her the basics of using it and, in return she gave me £5 and bought me a new tie as she said that the rather staid one I was wearing didnít fit my more outrageous, for the city of London in 1968, shirts and suits. She continued to keep in touch for several years. Telling me once that my help had allowed her to build her newly formed business into a very profitable concern. What happened to her when computers really took over I have no idea.

I donít think I mentioned that my father never drank, apart from a glass of cider at Christmas, so when I was invited to drinks at work I, initially, used to make up an excuse because, quite simply, I had never ordered in a pub and didnít really know what to ask for anyway. Mother had initiated my drinking at home but I used to join her and friends for a gin and bitter lemon and somehow knew that might not look too good among the lads. My new colleague, and fatherís ex-colleague, solved this by taking me out at Christmas. Motherís diary notes ďRichard had Christmas drinks, he drank many pintsĒ.

The year ended with the beginnings of my panic attacks, nowadays perceived as a mental health problem. I remember the occasion perfectly. It was Boxing Day. We were sitting at the table while father carved the cold turkey. For a second, I drifted off. I knew I had missed something and immediately panicked. I got up from the table and went to my bedroom and stayed there for the rest of the day. It was a feeling I hated. I have to be in control of my mind 100%, 24/7, which is one reason why I never, ever tried any drugs of any sort. So, if I thought I had lost it, for even that brief second, something was wrong. In later years I would announce I was going to die. In later years things were far worse. This time I just needed space to lie down. On reflection, I believe I was over tired. Five months in a very stressful job, being thrown in at the deep end, the excitement of Christmas plus those first drinks had all contributed to my tiredness and all it was is that for that one second, my body shut down.

These panics returned big time in 1974 and again I now know why but more of that later.